Work in Progress

I have contributed reviews, interviews and features to a number of magazines and platforms, some of which are no longer available. Scroll down for previous examples, with more soon to be added above.

mar

2023

ABSURD (What does it all really mean?)

Exhibition text

Post-truth news read a bit like a Kafka novel: the Queen is now a man, mini-budgets topple macro-economics, you can’t have an oven-ready cake and heat it, even fools no longer know the price of everything. According to the holy grail of fact [Wikipedia] the absurd is that which lacks a sense, often because it involves some form of contradiction.

Contradictions form the curatorial thread that links the works in ABSURD, an exhibition where nothing is quite what it seems at first sight: Lottie Stoddart’s canvases mimic ceramics, concrete masquerades as cardboard in James Lomax’ work, Ladina Clément’s weightless barbells defy reason and logic. Other examples may be less obvious in challenging our capacity to distinguish between certainty and implausibility, as in the case of Gillies Adamson Semple’s investigations into the nature of sonic and physical realms.

Jonny Briggs explores the boundaries between the self and the external world in surreal scenes reminiscent of Absurdist theatre, whereas Janina Frye’s creations contradict the function of human skin as a boundary to the outside world, acting instead as an interface that calls into question prevailing binary distinctions between animate and inanimate, nature and culture. Lea Rose Kara applies scientific research to test the limits of human knowledge; her ambiguous representations relying on the viewer’s participation in resolving the polarity between natural and manufactured dimensions.

Samuel Basset’s notion of painting for paintings’ sake could be interpreted as capturing the essence of Absurdist theory as he explores the meaning of contemporary life through an autobiographical lens while Rasmus Nossbring and Hyneck Martinec employ everyday moments and mundane objects to comment on past and contemporary manifestations of humanity. The latter offsetting his hyperrealistic painting with a dreamlike mural. Mark Jackson on the other hand speculates on the meaninglessness of human existence by evading corporeality, merging hard to decipher forms to evoke a sense of recognition in the viewer, with Johnny Hoglund taking a step further towards nihilism by working with the dust of paintings deemed failures.

With his unsettling sculptures that are at once familiar and eerie, Tom Bull responds to a changing landscape in terms of community and violence, tradition and progress, wealth and labour. While his sculptures may embody the most direct commentary on the current social and political environment, all works in the exhibition share a recognition of a fundamental void, a search for meaning, and ultimately freedom to define our own purpose – the basis of Absurdism, a philosophical revolution born out of post-war disillusionment.

Now as then, this absurd blend of mythology, humour and surrealism may help us escape impending dystopia.

OHSH Projects, 30 September – 30 October 2022

Art, Life and Everything

Review of Julie Umerle's memoir

I first met Julie Umerle at an artist talk that accompanied her solo exhibition ‘Rewind’ at the Bermondsey Project Space in 2016. I was immediately taken in by the calm confidence both the artist and her abstract paintings convey. Her practice has gone from strength to strength since with museum shows as far afield as Poland, the USA and China, as well as prestigious collaborations including Deutsche Bank at Frieze and an artist residency with Marriott Hotels.

‘Art, Life and Everything’ was published towards the end of last year and I first read it over the Christmas holidays. The term memoir started taking on real meaning as reading about Umerle’s memories brought back so many of my own, as she weaves her personal story around global events like the fall of the Berlin Wall, life before and after 9/11, or London specific memories of the Kings Cross Fire or the suicide bombs of July 2005, highlighting just how much the world has changed in the relatively short period of three decades covered in the book. Our paths could have crossed any number of times, at dodgy squats in 80s London, one of many of Nick Cave gigs or at ground breaking Brit Art exhibitions hailing the emergence of a new art establishment in the 90s.

London and New York are the backdrop to Julie Umerle’s story and I loved being taken back in time; wishing I had experienced a more bohemian Notting Hill to witness her first exhibition there in 1980, or fulfilled the dream of living in downtown Manhattan in the 90s – I was a lot less courageous than Umerle who arrived in New York on a one-way ticket determined to stay until money ran out. I’ve enjoyed reading her assessment of the cultural differences between both cities; insights into an unconventional family life, personal highs and lows and everything in between, are all told with subtle humour and without sentimental nostalgia.

I re-read the book during lockdown to remind myself that selective self-isolating during a global pandemic is easy compared to experiencing serious surgeries in true isolation and hooked up to a ventilator (I have a much better understanding now of exactly how gruesome this is). Accounts of her spinal operations in 1984 and 2004 are major time markers in Julie Umerle’s story so far, with the trauma of the latter undoubtedly a chief motivation for the book.

References to early feminist writing, in particular the notion of the personal being political, are even more relevant in our hashtagged times of #metoo and #blacklivesmatter; and while Umerle’s abstract paintings are not political at first sight, succeeding as a disabled woman against many odds and obstacles could be interpreted as a political statement of defiance against a world where everyone who appears different continues to be stigmatised.

Julie Umerle’s identity is defined by being an artist before being disabled and, above all, ‘Art, Life and Everything’ is an account of what it takes to be an artist. I recommend the book to anyone whose creative practice lacks motivation or direction due to current inhospitable conditions. Umerle’s story is one of creativity and self-expression conquering even the most chaotic circumstances.

While many believe that an artist’s career should be linear from graduation to being discovered and culminating in a museum retrospective, real life is a lot less predictable. The art world moves in cycles and artists are generally the first to suffer in a recession. Umerle’s memories of cancelled projects and struggling galleries in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash are not dissimilar to what we are witnessing now.

Her career progressed steadily for ten years from the alternative scene and showing at non-profit venues to gaining mainstream recognition with a solo exhibition at the Barbican. Returning to full-time education and moving from London to New York as a mid-career artist meant leaving history and context of her work behind and to start all over again. With New York an important place in the development of abstraction the move was an essential step to explore the historical and philosophical framework of her practice, which follows in the tradition of American artists like Barnett Newman, Agnes Martin or Robert Ryman.

Undisturbed periods of concentrating on developing one’s practice without the pressure of seeking out exhibition opportunities are essential for artists gaining confidence and purpose. This is where government grants and funded residencies play an important part. While the latter are often inaccessible to disabled artists, successful grant applications have been fundamental in Umerle’s development beyond the obvious benefit of providing time to develop new work and the prospect of future sales.

The author is generous with sharing her thoughts on running a successful practice; from the importance of record keeping and documenting work; on building up a professional support network of art suppliers, photographers and framers; the significance of critical reviews and exchanges with other artists; and on developing a wider circle of contacts as very few breakthroughs are due to pure chance. Umerle’s accounts make for inspiring reading and provide relatable context many guidebooks for artists are lacking.

Studio visits are often the first step to gallery interest and are very likely to result from introductions through third persons. Some exciting examples of people along Umerle’s journey and how they are connected wind through the book. She observes that recognition does not come from working in the studio and hoping to be discovered and has more to do with who sees the paintings when they are out in the world, and where they are shown.

The book is full of lived examples of how an artist’s environment is reflected in their work, from a practical level by adapting canvas size and materials to financial and spacial constraints; of careers developing at a different pace whether working in London’s industrial estates or to a backdrop of glamour and glitz at the heart of New York City; of the importance of rituals, whether preparing work for transit or repainting studio walls and floors before settling into a regular studio routine; to external triggers that can influence the work’s direction.

Examples of her paintings are reproduced throughout the book and illustrate the various stages of experimental and process-oriented approaches, of discarding and rediscovering colour, moving from individual paintings to working in series, from untitled to titled works. Abstract art is difficult to describe and I am taking liberty with paraphrasing Saul Ostrow who stated that were these paintings to succeed we should be able to say nothing about them.

published by FAD on 7 January 2021

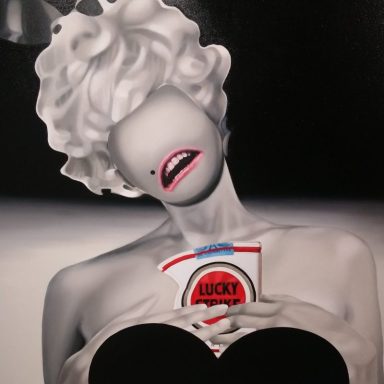

Catalogue cover with drink token. FAME by Teiji Hayama, Unit London, January 2020

Teiji Hayama, Lucky Bunny, 2019

Overheard at an Opening

Him: Why did you just take a photo of that painting?

Her: I'm still making up my mind...

Him: Once you have made up your mind, what will you do with the photo?

Her: I'll use it for my Instagram.

Him: Why would you post it on Instagram. Do you think it is good art?

Her: I will add it to my stories, just playing the game...

Him: So you think it's all a game, do you?

Her: Isn't that what people do... hide behind their mobile phones when they find themselves alone in a place?

Him: You came by yourself?!

Her: I was actually drawn to that painting over there... with the cigarettes... fags used to be the prop of choice when you were waiting... I've never smoked, so I'm making up for lost time with my phone now!

Him: Have you seen any good art recently?

Her: Went to Bruce Davidson at Huxley Parlour before I came here.

Him: So you do have taste! Will you be posting that on Instagram too?

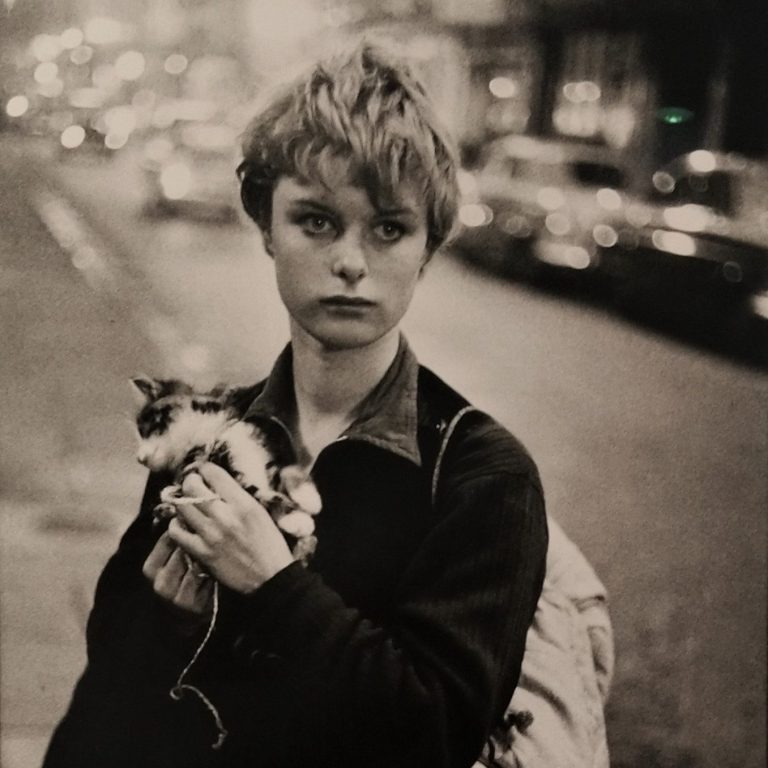

Her: Yes, I've chosen the one of the girl with the kitten...

Him: Not very imaginative, it's his most famous and the gallery used it as the cover. I would click right past you on Soulmates, too many cat women.

Her: People like kittens...

Bruce Davidson, Girl with Kitten, London, 1960

Her: So what brings you here, as it's obviously not the art on the walls?

Him: the free drinks! I'm about to use my second token.

Her: I'll be holding on to mine as a keepsake. Really love the idea!

Him: I'm sure U has a higher value in Scrabble...

Her: But it's worth one unit, I think it's very clever. I like the branding of this place, very consistent.

Him: I hate galleries that use a VIP cordon to show off how important they are … very pretentious.

Her: But it works! You know what and whom to expect. Very consistent brand proposition. I like the concept.

Him: Let me give you my card, I am an artist, you may like my work.

Her: OK, take one of mine...

Him: You have a card? You must think you are very important to carry business cards around with you.

The Museletter, Spring 2020 edition

Some thoughts on the future of artists' studios in London

With news spreading at a shocking rate of artists being evicted from their studios across London, a panel discussion about the future of artists’ studios in London was well timed and very well attended.

The event was presented by Frieze Academy and hosted by creative landlords Second Home as part of a series on art and architecture curated by writer and architect Edwin Heathcote whose 2015 essay in Apollo Magazine provides a good introduction to the dynamics of gentrification and short-sighted redevelopment.

Bold Tendencies and its failed bid for the Peckham multi-storey car park it had helped make ‘iconic’ was one of the examples cited in the article. Its founder Hannah Barry was one of the panellists. She was joined by David Adam, a globalisation expert who provides advice to cities and major organisations, and Candida Gertler, who runs public-private initiatives for safeguarding affordable and sustainable work spaces for creatives.

The overall tenor of the discussion was rather corporate as opposed to from an individual artist’s point of view. Examples of untapped potentials for the appropriation of existing spaces seem limited to empty garages and car parks which are predominantly owned by local councils. TfL and the NHS are other major landowners of underused spaces.

The conversation soon moved on to new-builds and how to best work with developers. In order to stand a chance of a proportion of developments to be made available to artists, the relevant decision makers need to be influenced at an early planning stage. Developers deal with huge costs and need to be persuaded that a sense of space, homeliness, sexiness – and community – can only be achieved with a truly mixed offer on ground floor level that goes beyond branches of Tesco Metro and Metro Bank.

New York and Berlin were stated as international success stories. Both cities recognise artists as agents of neighbourhood stability and vitality – as opposed to the more commonly held perception of artists as agents of gentrification. The latter is particularly true in London where artists have been replacing light industry before in turn being replaced by luxury flats, while local governments lack the funds or vision to oversee complex infrastructures and the Mayor of London’s remit appears limited to transport.

A major factor contributing to this major difference between London and other global cities is its patchwork of individually governed “villages” and gated communities in contrast to an urban planning model of zoning that includes dedicated creative industry zones. As a result London’s commuter towns are now screaming out for culture while there is a real danger of people deserting the city. As a general rule area plans with the direction for development are fixed for approximately 15 years and there is currently no nationwide approach for aggregating opportunities.

London’s population is rapidly increasing beyond its M25 boundaries and is joining other mega regions like New York’s tri-state area, or China. The significance of the sector is still underestimated here even though the UK’s creative industries contribute £84.1 billion to the country’s GDP, of which more than £5m are attributed to music, performing and visual arts. According to recent reports the capital generates 22% of UK GDP. The share is likely to be even higher when looking at the creative industries.

While it is difficult to quantify the contribution of artistic activity to a development’s success, the positive effect on people’s wellbeing is undisputed. Organisation like David Adam’s Global Cities and Candida Gertler’s Studiomakers make the case for the inclusion of artist studios and galleries at reduced rents. Artists are positioned as model tenants who hardly ever default on rent and who come with a universe of friends, peers and collectors who give new developments a certain flair.

Good management agents were stated as key to successful public-private partnerships. Clerkenwell Studios, the Harringay Warehouse District and the Yard in Hackney Wick were given as examples of successful negotiations with developers that resulted in mixed economies of people paying market rates and those on subsidised rates. A further example included successful negotiations with a Canadian developer who bought the street opposite Goldsmith’s and will integrate an annual street festival and a curated programme in a café.

I was probably not the only audience member leaving Second Home slightly deflated that evening. Very little reference was made to individual artists, especially those not yet established enough to even make it onto the radar of the few specialist management agents. Or the fact that the number of subsidised studios falls dramatically short of the artists made homeless by large-scale developments.

Sadly the picture is just as bleak when looking at exhibition spaces. While there are a number of entrepreneurial approaches to hosting pop-up events in commercial environments or the remaining opportunities for meanwhile spaces (i.e. those earmarked for development but not yet under construction), small galleries in particular are suffering in view of the steep increase in business rates (up to 45% in some London boroughs), alongside independent shops and grassroot music venues.

And as I was writing up my notes, I received an email from Re-Title that this independent information resource and promotional tool for emerging contemporary art was no longer sustainable due to the competitive nature of the digital market place and the dominance of big players like Google or Facebook; thus in a way mirroring the money-driven dynamics of the real estate market.

This post has now been sitting on my computer for several days as I hesitate to publish such dystopian observations without ending on a more optimistic note. While urban planners may not have factored in creative spaces on their blueprints, art has a habit of prospering even under the most adverse conditions and will search out opportunities away from the mainstream. So perhaps this is a salute to artists as agents of resilience and hope.

9 March 2017

Looking back at FutureFest 2016

Thoughts on balancing work, love, thrive and play

With more than a year passing since my post about slow media and hypercycling, this is an example of slow blogging! Another edition of FutureFest closed its doors for another year. And amongst many fast-paced panel discussions and technology-led presentations a couple of speakers stood out with their tributes to walking.

Will Self opened the event with an uncharacteristically cheerful plea for more playfulness and recounted his experience of walking to and from airports and the effect it has on the perception of time and space. The next day Brian Eno walked to Tobacco Dock from his home in Notting Hill, taking only a small sample of his Oblique Strategies cards and some loose pages of paper with him - the pioneers of electronic music keeps his presentations strictly analogue!

At the other end of the scale were: Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky who treated the audience to a guided tour of his iPad, taking in the history of songwriting, sound research and music technology; Soh Yeong Roh who introduced a whole range of companion robots from drinking buddies for lonely singles to swearing grannies for polite introverts; not to mention live microchipping of human volunteers.

FutureFest is a two-day conference at the intersection of research, creativity and innovation. Launched three years ago by Nesta (formerly the National Endowment for Science Technology and the Arts, now an independent charity), the 2016 edition had four overriding themes: Work, Love, Thrive and Play. But just like the boundaries between work and fun become increasingly blurred did most contributions tick more than one box. FutureFest itself is both a serious conference and a festival, attracting a predominantly professional crowd despite taking up an entire weekend.

One overriding theme was the significance of playful risk taking, starting with the lack of public space for children to roam in urban environments and the absence of fun in schools, through to the need for creativity in all departments and the importance of learning from bad ideas, no room for serendipity in recruitment and selection processes based on metrics.

While last year included contributions from Spain’s Podemos and Iceland’s Pirate Party and a video call with Edward Snowden, this year’s political contributions seemed the weakest link in a post-Brexit and pre-Trump limboland. The general consensus across all strands was that you can’t predict the future, you have to invent it - by breaking down existing structures from the grassroots up.

From a personal growth perspective Bill Burnett and Dave Evans gave practical advice on putting design principles at the core of creating a more satisfying life plan:

- What are the best parts of the life you already have?

- What would you do if what you do now didn’t exist?

- If money was no object and they wouldn’t laugh at you, what would you do?

Then create prototype scenarios to test your ideas and satisfy your curiosity before adjusting your career path.

Overall, FutureFest is positioned more at the heart of creative industries than at the wider intersection of science and culture, hence the concentration on technology and design-based disciplines. Yet it was the artists who made the robots come alive, put the fun into AR and reminded us of life beyond STEM. These and other examples also highlighted the relevance of interrelation between art and science across all aspects of modern life from healthcare and nutrition, education and entertainment, to urban planning and life after death.

And now on to something completely different, with just a fortnight to go until Frieze London opens its gates again, the fair’s Talks programme has just been announced. Themed “Borderlands” artists will share their take on the current political climate, refugee crisis and an increasingly divided society. We could do a lot worse than looking at art to make sense of the world.

21 September 2016

Are We Hypercycling to Cultural Exhaustion?

Time is ripe for a slow culture movement.

Earlier this year I attended an event on the theme of rebuilding our cultural landscape. An enlightening discussion was led by Dannie-Lu Carr who introduced us (a motley group of performers, artists, writers) to a new approach to repositioning creative processes at the core of cultural practice.

I hadn’t previously come across the term “hypercycle” and Dannie’s definition has not yet made it onto Wikipedia. She explains hypercycling as the rushing of cultural works towards public consumption before they are ready. The idea resonated deeply with my own experiences and was illustrated by some poignant case studies.

The author and playwright Jason Hewitt provided a stark example of being caught in a hypercycle upon finding a publisher for his first novel which took four years to complete. The contract committed him to produce a follow-up within 14 months, in addition to promoting the launch of his debut.

Every musician and music fan has heard of the Difficult Second Album Syndrome, an affliction made worse by the decline of physical releases in favour of digital downloads and streaming. Add to this obvious hypercycle the commercial pressures faced by the major record labels, and you could fear for the future of music and culture as a whole.

Former Island Records manager Marc Marot highlighted the dilemma faced by labels who are reluctant to let go of the business models (and profit margins) that served them so well in the past. He used to enjoy the freedom and integrity to select his roster of artists based on excitement, instinct and long-term promise. This allowed him to truly nurture his artists’ creative process. He has since had to adapt his approach to meet short term targets and write predictable success stories.

By sheer coincidence, I attended one of PJ Harvey’s recording sessions at Somerset House the very same day as hearing her former manager’s account of how his A&R style dramatically changed. Needless to say, witnessing the rehearsal and recording process of one of the UK’s most exciting and talented artists was an inspiring and uplifting experience. But how many less established musicians have the opportunity to lock themselves in a studio, write an album – and be paid for the process?! And would an as yet undiscovered Polly Jean be given a chance under the current obsession with get-famous-quick schemes?

Hypercycling is not just prevalent in the private sector. Quite the contrary. Many artists and organisations spend a lot of time and energy on painstakingly completing funding applications instead of concentrating their time on the creative process itself. By the time grants are approved many projects have to be rushed, thus resulting in a much less satisfying experience for artists and audiences.

My personal hypercycle was that of trying to continue to nurture personal relationships and uncover new trends while having to meet increasingly short-term (and short-sighted) targets driven by economic forces rather than audience needs. How do you generate year on year growth in a declining market with fewer people fulfilling more tasks? My individual solution was to jump the sinking ship and reclaim autonomy by first moving into freelance, then leaving the media industry altogether. Progress since has been slow and gentle; completing a series of crestcycles (a concept developed by leadership coach Dannie-Lu Carr) has been immensely satisfying and reinforced my trust in the right person appearing for the right thing at the right time.

The responses to the effects of hypercycling, or the burnout syndrome it can lead to, tend to be very individual. However, there are examples of movements with the collective aim of slowing down - whether it be our approach to food, city living or even media – and achieving individual wellbeing and universal sustainablilty.

Since starting to write this piece I have attended FutureFest, a thought provoking conference lead by innovation charity Nesta, and would like to end by quoting leading brand consultant Ije Nwokorie who believes that creativity is everything that automation can never be:

Time is ripe for a slow culture movement.

17 March 2015

© 2023